ARTICLES AND REVIEWS

Heaven17 - The making of Pleasure One

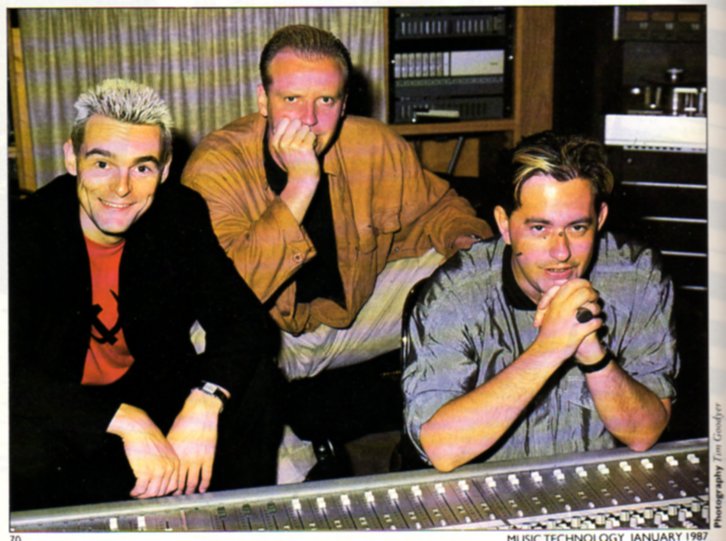

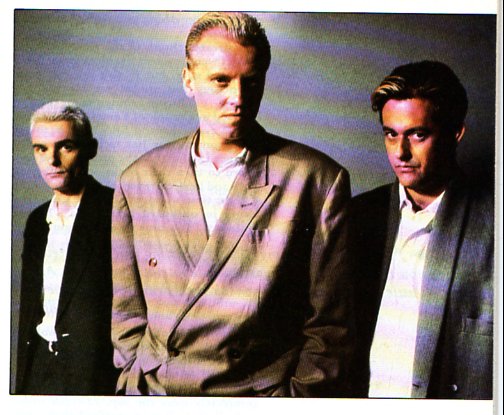

Five years after splitting from the Human League, Heaven 17 have just released their fourth album of hi-tech pop. And they may be doing their first live gigs. Five years after splitting from the Human League, Heaven 17 have just released their fourth album of hi-tech pop. And they may be doing their first live gigs.Interview by Tim Goodyer. LONG BEFORE HEAVEN 17 was even a glimmer in the eyes of its founders, there was the Human League. Formed in Sheffield in 1977. the band comprised Philip Oakev. Martyn Ware, lan Craig Marsh and Philip Adrian Wright — four men who sought to replace conventional instruments with synthesisers and a tape recorder. Their first album, Reproduction, appeared in 1979. Concessions to commerciality were few, and in spite of the liberal attitude of the time, the future success of League couldn‘t have seemed further away. “The whole thing was accidental“. explains Ware. “The Human League was basically an experiment in electronic pop: the only rule was there were to be no acoustic instruments, everything was to be done with synthesisers. Unfortunately the synthesisers around at the time weren‘t capable of doing what we wanted them to do, even though we thought they were. “At that time we had no idea we were even capable of landing a record deal. Every group nowadays assumes they a right to sign a contract; in those days it had never occurred to us. The facilities weren‘t even there to do demos unless you really put your mmd to it. Now anyone can knock out a demo of reasonable quality on a Portastudio.“ ...So ideals were sacrificed, the presentation changed. and a contract with London‘s Virgin Records resulted. But it wasn‘t long before the first differences of opinion began to show. “We were an instrumental group originally“, says Ware, “hut we got Philip singing and the whole thing took off. Then it stagnated for a couple of years when we didn‘t have any commercial success. Lack of success in a group is the major cause of tension, it‘s the reason most groups split up. Philip wanted to be a pop star in the old sense of the word, so we started talking to each other less and less and finally split up.“ Oakey added backing singers Susan Sulley and Joanne Catherall and guitarists Lan Burden and Jo Callis to the League, whose Martin Rushent-produced Dare brought them fame and fortune, and established the drum machine as an essential part of the “new“ Pop music. More recently, the slimmed-down Human League have topped the singles charts with ‘Human‘, proving that they‘re as capablc of writing a catchy melody and a classy arrangement as they‘ve ever been. Ware and Marsh, meanwhile, formed Heaven 17. The former continues the story. “We got Glenn (Gregory) in as an old friend and it turned out he was a much better vocalist than we envisaged. lt occurred to us during the transitionary period that the music we were listening to wasn‘t electronic music. “lt often happens that the music you listen to for enjoyment isn‘t what you create yourself. We started listening to a lot of American dance music, so that‘s what we aimed for with Heaven 17. We still regard ourselves as a black-influenced group, although very few people seem to understand that. We‘ve always been regarded as some sort of wacky electronic group, but we‘re not obsessed with equipment. “In America we thought we‘d have a really bad time, hut they h.‘med in on what we were really about. In America they listen to the music and don‘t pay too much attention to the image, whereas here the image comes first. lt‘s a bit sad really, because it means there‘s no incentive to make interesting music.“ In 1981, Heaven 17‘s idea of interesting music was a dancefloor smash entitled We Don‘t Need This) Fascist Groove Thang‘ and an LP Penthouse and Pavement. Released concurrently with Dare, Pentbouse and Pavement went gold on both sides of the Atlantic, putting Heaven 17 firmly on the map in their own right. Their success story continued through 83, with a follow-up album, The Luxury Gap, only to stumble a year later with an expensive mistake called How Men Are. Now Pleasure One marks Heaven 17‘s return to the public eye, and to more conventional values.  The Human League was basically an experiment in electronic pop: the only rule was there were to be no acoustic instruments, everything was to be done with synthesisers." FRESH FROM FILMING videos for two tracks from the album — ‘Contenders‘ and ‘Trouble‘ — it‘s clear the trio feel happier with the results of Pleasure One. Lounging comfortably at London‘s Townhouse studio complex, Gregory explains the reasons for filming in Los Angeles. “We put it all together over there. lt‘s got 50 black dancers in it and was choreographcd by someone called Otis — how can you go wrong with someone called Otis? lt felt a bit weird at first going into the dance studio and him telling me to ‘go through my stuff‘. I felt a little embarrassed but I just had to grin and bear it. I must admit, there were tinles when I was ready to put on my coat and go home. We‘ve only seen the basic shots being transferred from film to video, but they look good. We‘ve got our fingers crossed.“ So what of the album itself? How Men Are cost something in the region of £200,000 to make, hut this time the band recorded extensively in their own studio in Twickenham. Ware explains. “All the backing tracks were done at our 24-track at Jan‘s place, and then we recorded the live musicians at Red Bus. “lt‘s a little easier now because we used to get all our ideas together round Mart‘s house with a little Casio. But we found it very wasteful doing demos and then rerecording them in the studio; you do things on demos that for some reason you can‘t recreate when you get into the studio. lt‘s a bit futile trying to recreate something you really like anyway, so the next logical step was to get a studio where we never had to do demos that didn‘t become part of the end result, or where you couldn‘t throw away individual components. You shouldn‘t have to try to duplicate something you really like in the first place.“ A sizeable chunk of the How Men Are budget went towards the hire of expensive outboard gear, but in this area at least, technoiogy has smiled on Heaven 17. Instead of hiring equipment, they‘ve invested in a couple of Yamaha REV7s, an SPX9O and a Roland SRV2000. Is this a false economy, or has technology really advanced so far that the professionals can afford to turn their backs on the likes of AMS and Lexicon reverbs? “Last time we spent about 20 grand on hiring in outboard gear alone“, Marsh confesses. “This time we spent about £300, but I think it‘s totally down..to technology. We‘ve got the same amount of reverb but we‘ve been able to do it cheaper. “To a certain extent it‘s a change in attitude as weil. Last time we went completely over the top, 72-track mixes and all that. l3ut we realised that, even though it made it sound great technically, it knocked the heart out of the songs. You spend so long concentrating on the minutiae of the mix that you lose sight of their true value. lt‘s a risk you run. A lot of people don‘t suffer from it because they don‘t pro‘duce their own albums. When you‘re actually involved in every stage of it, yu have to keep an overview. “We asked another producer to do it but he had a film project which represented a lot more money. He also wanted us to go out and use a studio in LA, which we didn‘t want to do. lt‘s a trick they all pull nowadays — not only do they pocket the advance, they also get huge amounts of money frorn the use of their own studios.“ Instead, it was Ware who bore the brunt of the production burden, though he is eager to stress the band‘s democratic approach to making music. “1 do most of the final decision-making but we all collaborate on it“, he claims. “We‘re all in on every part of the creative process: we all write the music together, we all write the lyrics together, and we all work on the production together.“ “Drum programming was very exciting wben it started, but now there‘s so much of it around it‘s not novel any more. All the little tricksyou can do, even with real drum sounds, have been done."

THE INCLUSION OF a live rhythm section is another new direction for a band who had previously helped pioneer the use of programmed rhythms. “lt wasn‘t that we hadn‘t used live musicians before“, protests Marsh, “hut the difference is how we‘ve used them this time round. We‘d had people like Simon Phillips guesting on the odd track, but never this extensively. The basis of all the percussion used to be the LinnDrum or whatever, but we liked the idea of getting the bass and drums down together as a live unit. We recorded 11 tracks in three davs like that, one after another so they all have this live feel to them. Before it had been much more fragmented — we‘d pulled people in months apart to put things down.“ “1 think it‘s quite a subtle difference‘. continues Ware, “because it‘s the arrangement that makes a song sound the wav it does. Our style of arrangement hasn‘t changed that much, it just sounds a bit more lively than the last album, which was all Fairlight-based. This time there‘s onlv one song that uses a Fairlight rhythm track. “Drum programming was very exciting when it started, but now there‘s so much of it around it‘s not novel any more. All the little tricks you can do, even with real drum sounds, have been done — the extremely fast snare fills and bass drum rolls and all that. lt might be interesting for groups that arc just starting, but we‘ve been doing it for so long that we thought we‘d go back to the old band setup.“ The transition from electronic to human drumming sounds straightforward enough, until you consider the problems of writing rhythm patterns for an absent drummer. Difficult enough in itself, hut in Heaven 17‘s case, they didn‘t even know the identity of the drummer until after the songs on Pleasure One were written. “We didn‘t know at the time“, savs Ware, “but Preston (Heyman, the drummer the band eventually chose) prefers to play to a dick, so a lot of the original Linn rhythm patterns didn‘t get used — which is cool. Anyway, you have to play around a drum pattern, it‘s like an arbitrarv rhythm; you finally decide what you want later on.“ And in more general terms, Heaven 17‘s newly adopted work method has already produced sufficient material to form the basis of Pleasure Two. Meanwhile, a glance at the sleeve of Pleasure One reveals the rhythm section to be bassist Phil Spalding, and the musician responsible for the slick guitar work to be one Tim Cansfield. “lt makes it a lot easier when you‘ve got intelligent musicians to work with“ says Ware, “because they bring their own influences to a track. Assuming you pick the right musicians in the first place, that‘s a very valuable thing. You don‘t have to sit for hours pondering what on earth can go into that bit of the track; they can usually come up with something you wouldn‘t ever have thought of. “lt‘s taken a bit of the pressure off us, hut we still always write the basic structure of the song — chord structure and rhythm patterns — before anyone else hears it.“ The newly established practice of collaborating with other musicians has given Heaven 17 more than extra pairs of hands with which to perform their music, for Gregory, Ware and Marsh place a higher value on their songwriting and arranging skills than they do on their musicianship. “We‘re not musicians. Technically we can‘t play a lot of the stuff that‘s on the albums, but our arranging capabilities have developed and we write a lot more interesting music now we‘ve got a better grasp of mood and feel. We design the albums for our own pleasure. We regard ourselves as the directors of the film, rather than the actors.“ With the Fairlight all but retired, the ubiquitous Emulator II has becorne the band‘s instrumental workhorse. But any sampler is really only as good as its samples. “lt drove us mad“, recalls Gregory. “We spent about two months sampling things in Martyn‘s front room. After a while we started talk-talk-talking like this — seriously! lt was incredibly brain-numbing. lt got to the stage where we could only do about an hour a day.“ Ware interrupts: “A lot of groups employ a programmer now, but as soon as someone learns to program they realise just how easy it is to create things for themselves. They don‘t want to do it for anvone else; that‘s like doing all the spadeyork with none of the rewards. “So I bought the CD ROM for the Emulator right towards the end of rccording. That‘s got like 500 banks of sounds that would have taken us SiX months to sample. lt only coSt about £1500 and it‘s expanded the capability of the Emulator II bv at least three or four times.“ Then again, the danger with using ommercially available sounds is that everyone else has access to them too. Ware doesn‘t consider this a problem. “lt‘s not a problem if you acknowledge that it is a problem — then you can avoid it. There are so many sounds that it‘d take vou months to listen to them. We‘ve got about the same number again of our own samples if you include the Fairlight, but there‘s no way we‘re going to exhaust them. lt doesn‘t actually matter: unless vou‘re putting a particular sound into a mix as a solo feature, you‘re never going to recognise it. “A lot of electro groups are still using the same old sounds off the Fairlight — the Orchestra 5 and the same old brass -amples — because they don‘t know how to use it. That‘s really boring; you can hear them on hundreds of records. ‘We‘ve gone through the theory and the practice, and the sounds you choose ire much more relevant than whether someone else is using them. Depending on how you use a sound in a track, it sounds entirely different anyway. The problem is more that you‘ve got too much choice; that‘s why a lot of people can‘t cope and just use the sounds that they‘ve heard on other people‘s records. We tend not to use Emulator sounds as features in a track; we mainly use them for bed sounds and atmospheric things that aren‘t too high in the mix.“ “We‘re all in on every part of the creative process: we all write the music together, we all write the lyrics together and we all work on the production together.“

THE GAP BETWEEN How Men Are and Pleasure One could be construed as a period of reconsideration for the artists, but Ware is adamant that a hectic work schedule is a far from healthy way to produce music. “There‘s nothing worse than living your entire life for your career. lt‘s good to have a little mental space to lead a sane life. No wonder a lot of traditional rock groups go off the rails because there‘s such immense pressure even in the time we spend working. I know I go mad to a certain extent when we‘re in the studio — I think we all do, it‘s like cabin fever. When you‘re concentrating so hard on something it‘s very straining.“ But Pleasure One hasn‘t been the only project to occupy Gregory, Ware and Marsh in the two years since How Men Are. Back in 1982, the same three men formed the British Electric Foundation, an Organisation whose aims seem to have cleverly evaded definition, but which produced an album of unlikely Pop songs, arranged for unlikely combinations of electronic instruments, and sung by a still more unlikely assortment of singers. The album was titled Music of Quality and Djstjnctjon, and it saw Paula Yates, Sandie Shaw and Gary Glitter singing songs like ‘Suspicious Minds‘, ‘These Boots Arc Made For Walking‘ and ‘You Keep Me Hanging On‘. Now the BEF is only Martyn Ware‘s production title, but it is no less active for that. One of the stars of Music of Quality andDistinction was Tina Turner — and as it turns out, she is also the BEF‘s latest production project. “I‘m pretty picky about what I do because I don‘t have much time away from Heaven 17, but I did three tracks for the Tina Turner album“, says Ware. “They were all cover versions because 1 wouldn‘t have felt comfortable writing anything for her — let‘s face it, it‘s a bit of a challenge to write anything for a voice like that — but none of them were actually used. One was Al Greene‘s ‘Take Me to the River‘ which 1 thought was brilliant — and so does everybody else l‘ve played it to. 1 hope it‘ll see the light of day in some form; if not, we may buy the backing tracks off her and use it ourselves.“ In addition to the BEF, Heaven 17 have their eyes set on the big screen — or at least the sound that accompanies the pictures on the big screen. And in the meantime, television advertising has proved to be a lucrative step up the audio-visual ladder. “We did the soundtrack for a Kellogg‘s Start advert, says Ware. “That was the first time we‘d ever recorded anything with SMPTE. Working that directly with images brings lots of ideas flooding through. With a video you create the images around how you conceive the track. With film you have to design sounds around what‘s happening on the screen. “We want to start doing real film soundtracks but it‘s difficult to break into. lt‘s very cliquey, like an old boys‘ club, but we did have one boxing match with a French film. We were supposed to do a complete soundtrack but after working on it for two or three months, we pulled out. We did gain a small insight into how incredibly difficult and time-consuming everything is, though it‘s not actually so difficult to do the music, it‘s more politically difficult. linagine having ten executives in a room each with a different idea of how it should sound. At one point we looked around the studio and there were about 30 people gibbering away in French, so we left. They probably didn‘t even know we‘d gone for half-an-hour. “But it‘s a good, creative, well-paid job.“ An air of confidence comes into Ware‘s voice. “We‘ve certainiy got the equipment and the wherewithal to do it. We could do the best horror film soundtrack ever.“

|

APART FROM THEIR recorded success, one of Heaven 17‘s claims to fame is that, with the exception of Gregory‘s

performance of ‘Fascist Groove Thang‘ on the Red Wedge tour in Bradford, they‘ve never played live.

“1 dicl ‘Fascist Groove Thang‘ live with the Style Council and Junior“, admits Gregory. “lt was

really weird — our one and only live gig, Bradford on a Tuesday night. They wanted me to do another one in London but 1

said no, let‘s not overdo it...“ One of the main reasons for Heaven 17‘s aversion to the concert hall is

the money lost touring in the early days of the Human League, but things arc no longer that simple, as Ware explains.

“1 don‘t think having a high public profile is that relevant these days. Ob— viously if you like live music

it is, but there aren‘t that many people who go to see live concerts, and it‘s not an automatic assumption that

somebody who goes to a concert buys the album. When 1 was 17 or 18 it didn‘t matter who you went to see. you‘d go

out and buy their album afterwards. “Whether we seil records or not is down to the quality of the records — as

we‘ve proved. We‘vc never toured as Heaven 17. yet we sold 3,000,000 copies of The Luxur-v Gap. If people

don‘t buy the records it‘s because they‘re not good enough. We face up to that.“ “What you need

to sell records is not a tour, it‘s the total backing of your record company“, adds Gregory. “We feel

we‘ve got that now. When we first split up from the Human League they were very sceptical; they decided not to promote

the first album. But that sold about five times more than any League album had.“ Ware continues: “Nobody ever

mentions that touring isn‘t just a strain, it‘s inteliectuaily boring because you‘re reproducing the same

old stuff every night. That is, unless you need that constant ego boost of people cheering you — I think that‘s

why a lot of people really want to tour.“ “Concert tickets over here arc so expensive and so often the bands arc

terrible“. resumes Gregory. “Some bands just weren‘t meant to play live, a lot of them aren‘t really

musicians in that sense, so they‘d be better off doing as we do.“ In this area, at least, Heaven 17‘s

attitude looks set to remain as it is, with the single exception of an appearance on The Tube. The line-up that put in a

powerful perforniance of ‘Contenders and ‘Trouble‘ on that occasion saw Gregor‘. assisted on vocals

by Carol Kenyon and Martyn Ware, who‘d temporarily abandoned his technology. Marsh brushed th dust off the Fairlight,

and a second keyboard player took command of th Emulator II. The rhythm section was th same combo that produced so much

enthusiasm earlier in our conversation. Yet the band‘s recent signing to Virgir America may weil see Heaven 17 on th

road in the States. And if it does, it seem likeiy the line-up will take a similar form to the one listed above. “I

think we may get pressure now“, sav Gregory, “because touring does mear something in America. I‘d like to

say w won‘t bend under that pressure, but think it is quite possible.“ “The oniy thing that makes it

possible i the way we‘ve done this album“, muse Ware. “I think it would have been impos sible had it been

the last album. We‘d us live musicians for everything that‘s live or this album: bass, drums, guitar an

keyboards. That way we could do passable representation with very littl need for anything else. We could do ‘rocl

hour‘ versions of older material, lik Status Quo.“ A sudden realisation strikes Gregor “I‘d have to

learn the lyrics!“, he explodes “That‘s the great thing about recording — can do the album and forget

about it. With luck, Heaven 17‘s fans won‘t find Pleasure One so easy to forget.

APART FROM THEIR recorded success, one of Heaven 17‘s claims to fame is that, with the exception of Gregory‘s

performance of ‘Fascist Groove Thang‘ on the Red Wedge tour in Bradford, they‘ve never played live.

“1 dicl ‘Fascist Groove Thang‘ live with the Style Council and Junior“, admits Gregory. “lt was

really weird — our one and only live gig, Bradford on a Tuesday night. They wanted me to do another one in London but 1

said no, let‘s not overdo it...“ One of the main reasons for Heaven 17‘s aversion to the concert hall is

the money lost touring in the early days of the Human League, but things arc no longer that simple, as Ware explains.

“1 don‘t think having a high public profile is that relevant these days. Ob— viously if you like live music

it is, but there aren‘t that many people who go to see live concerts, and it‘s not an automatic assumption that

somebody who goes to a concert buys the album. When 1 was 17 or 18 it didn‘t matter who you went to see. you‘d go

out and buy their album afterwards. “Whether we seil records or not is down to the quality of the records — as

we‘ve proved. We‘vc never toured as Heaven 17. yet we sold 3,000,000 copies of The Luxur-v Gap. If people

don‘t buy the records it‘s because they‘re not good enough. We face up to that.“ “What you need

to sell records is not a tour, it‘s the total backing of your record company“, adds Gregory. “We feel

we‘ve got that now. When we first split up from the Human League they were very sceptical; they decided not to promote

the first album. But that sold about five times more than any League album had.“ Ware continues: “Nobody ever

mentions that touring isn‘t just a strain, it‘s inteliectuaily boring because you‘re reproducing the same

old stuff every night. That is, unless you need that constant ego boost of people cheering you — I think that‘s

why a lot of people really want to tour.“ “Concert tickets over here arc so expensive and so often the bands arc

terrible“. resumes Gregory. “Some bands just weren‘t meant to play live, a lot of them aren‘t really

musicians in that sense, so they‘d be better off doing as we do.“ In this area, at least, Heaven 17‘s

attitude looks set to remain as it is, with the single exception of an appearance on The Tube. The line-up that put in a

powerful perforniance of ‘Contenders and ‘Trouble‘ on that occasion saw Gregor‘. assisted on vocals

by Carol Kenyon and Martyn Ware, who‘d temporarily abandoned his technology. Marsh brushed th dust off the Fairlight,

and a second keyboard player took command of th Emulator II. The rhythm section was th same combo that produced so much

enthusiasm earlier in our conversation. Yet the band‘s recent signing to Virgir America may weil see Heaven 17 on th

road in the States. And if it does, it seem likeiy the line-up will take a similar form to the one listed above. “I

think we may get pressure now“, sav Gregory, “because touring does mear something in America. I‘d like to

say w won‘t bend under that pressure, but think it is quite possible.“ “The oniy thing that makes it

possible i the way we‘ve done this album“, muse Ware. “I think it would have been impos sible had it been

the last album. We‘d us live musicians for everything that‘s live or this album: bass, drums, guitar an

keyboards. That way we could do passable representation with very littl need for anything else. We could do ‘rocl

hour‘ versions of older material, lik Status Quo.“ A sudden realisation strikes Gregor “I‘d have to

learn the lyrics!“, he explodes “That‘s the great thing about recording — can do the album and forget

about it. With luck, Heaven 17‘s fans won‘t find Pleasure One so easy to forget.