ARTICLES AND REVIEWS

THE FLUKES OF

HAZARD

THE FLUKES OF

HAZARD

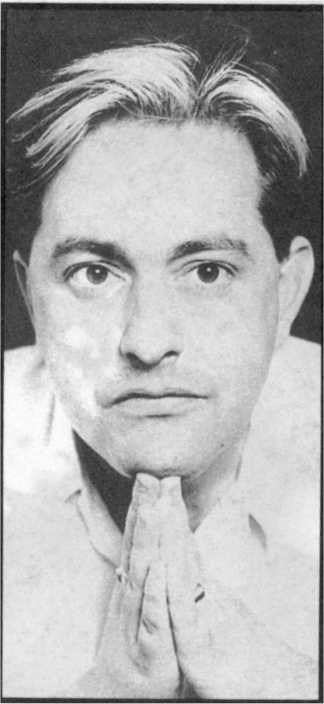

IT'S all very jolly this. HEAVEN 17 are keeping me comfortably amused in Martyn ' Ware's Westbourne Park sanctum. Martyn, possibly twice the size he used to be, is in the process of giving his property away. "There's the bookcase," he announces. "Take what you want." The bookcase is nailed to the wall so I settle for a book. "Fungus The Bogeyman" has an amorous inscription scrawled inside it so I plump for "Hollywood Babylon." I'm hoping hell start giving the furniture away next. But it stops there.

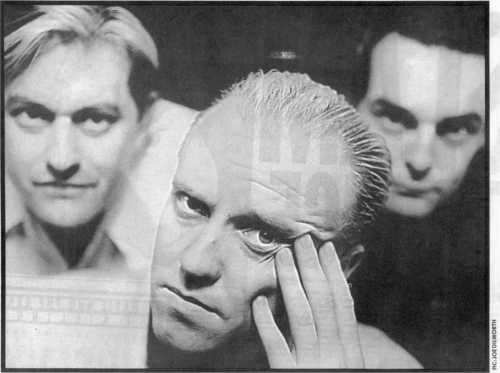

Gregory, Craig-Marsh and Ware are proving impossible to sneer at. All round good guys. We are gathered to find out why Heaven 17 are still pluckily soldiering on after all this time. Seven years since the mischievous white funk dash of "(We Don't Need This) Fascist Groove Thong". Five years since their lost truly compulsory chart plunge, "Temptation". There have been gently persuasive moments since then, no mistake. "Crushed By The Wheels Of Industry" was determined enough. "And That's No Lie" was just about long and lithe enough, Gregory never sounding quite so endearingly uninvolved. Nothing, though to blister your soles about. For longer than we care to recall, Heaven 17 have been watching themselves go through the motions. At least that's how it sounds. Forever getting all crafty and conceptual, but hardly delivering. Perhaps that's the point. And maybe not.

"You're

saying that you don't know who we are anymore," says Martyn, "that you don't

know what we're doing around here. Well, we wonder all this too. It's interesting

in a way. It's not that we're an anachronism. We're totally out of the mainstream

and for apart from anything that's categorizable. We are a very odd group.

There's no doubt. We're completely adrift, that's all. We don't even have

a corner to ourselves. We just do what we do and there's nothing we can do

to change that. It's either popular or it isn't. It's not in our control

if it's either. When it was successful, it wasn't any different to us than

what we are doing now. Either you're popular or you're not. If you start

chasing the dream, it just disappears. We are not going to get there by altering

our style. I'm not even sure that we would like to be perceived in a clearer

way. It's not as if we're going out of our way to make it clearer.

"You're

saying that you don't know who we are anymore," says Martyn, "that you don't

know what we're doing around here. Well, we wonder all this too. It's interesting

in a way. It's not that we're an anachronism. We're totally out of the mainstream

and for apart from anything that's categorizable. We are a very odd group.

There's no doubt. We're completely adrift, that's all. We don't even have

a corner to ourselves. We just do what we do and there's nothing we can do

to change that. It's either popular or it isn't. It's not in our control

if it's either. When it was successful, it wasn't any different to us than

what we are doing now. Either you're popular or you're not. If you start

chasing the dream, it just disappears. We are not going to get there by altering

our style. I'm not even sure that we would like to be perceived in a clearer

way. It's not as if we're going out of our way to make it clearer.

'We are weird. But we don't appear to be weird. Which makes us even weirder. We don't even get credit for being weird. We have a definite dislike for the conventional path, even if it's a self-destructive one. These are the dark ages for music in this country. To be on the outside of it is not necessarily a bad thing. We've been touched by commercialism but we haven't been sucked in totally."

THIS isn't the Heaven 17 post-mortem by the way. But, while Heaven 17 are complacent and neglectful enough to issue a record as faint-hearted as "Teddy Bear, Duke Psycho", their latest LP, it seems like a good time to stop and wonder why this peculiar group even bother any more. It seems like a damn fine time to ask Heaven 17 who the hell they think they are and why they hum and haw like this, at a time when their conceits and their exposures have never been so far removed.

Port of the problem for Heaven 17,1 tell them, is that they promised us so much to begin with. "Music For Stowaways", BEF, the grandly conceived group image, grand claims to blast apart the accepted notions of pop production, grand plans to make themselves a self-sufficient business unit, infinite dreams and schemes... Now that they have long since become the squarest of pop concerns, they can hardly blame wet blankets like myself for wondering how it all turned so, well, square.

"Sure,' Martyn agrees. "That was the original idea but we became a band in the real sense of the word. It was naive and highly unrealistic of us to assume that we could do all that. The fact is that Heaven 17 became so successful so quickly, we didn't have time to do anything else."

It was as though the process at making records became more relevant to them than the records themselves. After Heaven 1 7's first few brushstrokes, adding much to the cock-eyed audacity of 1982's rejuvenated charge, it did not take too much insight to see that, beyond all the bustle, there lurked a muso mentality that would soon take its toll and poke through. No wonder the irony of their "Penthouse And Pavement" sleeve (spoofing the idea of the group as earnest pin-striped executives] was lost on most people.

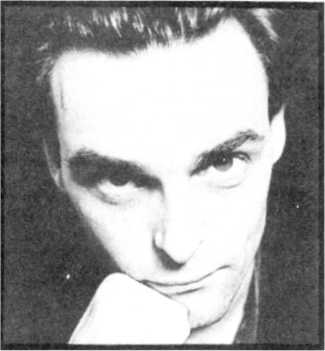

"Not

that the businessman image was a gimmick to begin with," Ian points out.

"We were just pointing out that music is a business. We weren't saying that

we were approaching it any differently. It's the way that everyone approaches

it, but they don't necessarily own up to that."

"Not

that the businessman image was a gimmick to begin with," Ian points out.

"We were just pointing out that music is a business. We weren't saying that

we were approaching it any differently. It's the way that everyone approaches

it, but they don't necessarily own up to that."

Unfortunately, it rebounded on the group in ways they had never conceived.

"It struck a chord in the audience for the wrong reasons,' Martyn explains. "They took it literary. The new acquisitive, upwardly mobile youth. The sleeve of 'Penthouse And Pavement', was seen to justify all that. We thought it was an obvious piss-take. What we were actually trying to comment on was the total dishonesty of the old style of rock musician. The ones who claimed they had nothing to do with the business and didn't want anything to do with money, who believed they were artists with a capital A. In fact, the music business is the most capitalist business you could conceivably imagine. It's totally based around the capitalist ethos. But we were coming clean about the fact that we were playing the same game as everyone else. It was supposed to be witty but wit, it seems, is very difficult to get over.

"We simply like the idea of making people think a little bit. That's all we've ever claimed to do. Now, I guess we're in limbo. It's like The Labour Party. It's not that they've moved anywhere politically. It's just that everything around them has shifted. I think we're in a similar position. Of course, it doesn't help when people miss the joke. If the album sleeve was a photo of us with clown's noses, sticking our tongues out, they'd still be looking for the implications of the red nose. It's subtle irony."

'When we do it," Glenn continues, "we think it's enormous. It's like great big targets painted on our bums. Obviously, people don't see it like that."

"Teddy Bear, Duke & Psycho" is the sound of a group in limbo, fidgeting in public. A spineless, aimless techno-pop whirl, for the most part. The highly entertaining, profoundly hyperbolic, press-release talks about the sumptuousness of the moment, but I can't find it anywhere. It leads us astray with red herrings like Bernard Cribbins, Bryan Forbes" 'The Stepford Wives", Cecil B De Mille and Godard's "Hail Mary" but, all too familiarly, the centre is not so chewy. Not nearly.

were'Martyn acknowleades. ou, - .., learnt a lot which we hope translates into what we create. It does sound a lot less impetuous these days. Of course it does. It's forced to. At least we started out impetuously. Most groups these days never get that far.

"It's not that this LP is necessarily odd. It's not just homogenous. We deliberately made it that way. To cater for a record company, it's ideal to carve out your little niche in the market and stay there until you've run out of ideas. We don't do that. We've never done that. What the f"' are we? It's a damn good question. We are three separate people with a specifically socialist viewpoint which sometimes infiltrates the content of our songs. We are more interested in descriptive music than fitting into any bag. When all is said and done... we probably have a better time than any bastards on Earth."

Since the last Heaven 17 LP, Martyn Ware has earned himself an indecently large bag of money producing albums for Tina Turner and Terry D'Arby. His latest ambition is to produce 1975 revivalists, The Eight Track Cartridge Family, because he likes the name and it will look good next to the other two names on his CV. Having loads of money is "all right really" but he's not using it to finance the band. "That would be chucking f***ing money down the drain," he half-jokes.

While we are not quite holding the post-mortem on Heaven 17, Ian "I am the quiet one" Craig-Marsh is having his car clamped outside. He's also recently blown £7,000 on gold investments.

"Sometimes you get on the bus and sometimes you miss it," Glenn reasons.

"And sometimes," laughs Martyn, "the bus runs over you."

He shrugs hopefully.

'We'll come out of the end of the tunnel, someone will claim that we're gods, and all of a sudden we'll be huge again.

A jolly long wait begins here - JW